Behind the Book: The Guard

In early 2011, my family and I lived near the US embassy compound in Amman, Jordan—so near, in fact, that our apartment was inside the outer guard ring. I was very happy about this situation. Two weeks after my three-year-old daughter and I arrived, my husband was sent to Italy indefinitely to help with a NATO mission. Meanwhile, the Arab Spring was taking root and there were protests outside of the Syrian embassy, protests outside of the American embassy, protests in the rural areas outside of Amman over the high costs of cooking oil and bread, and protestors in Amman demanding political reforms. Then Osama Bin Laden was killed by US Special Forces in Pakistan, which was seen by many as another US invasion of a country’s sovereign territory. Prime-time news was filled with burning American flags.

So you can imagine how much I loved seeing the US embassy guards standing at the gates.

Everyone stationed at the embassy had to attend a Regional Security Brief within a few days of arrival. We were told to change up our driving routines in order to make it hard for us to be followed, to look under our vehicles for explosive devices, to not drive beyond Amman city limits after sunset, and to always let a fellow American know when we went on a trip.

We had also been warned about our Western ways, with a special emphasis on how American women needed to be sensitive to this culture quite different from our own. It was recommended our clothing cover us from wrist to ankle. That we be aware conservative Muslim men would feel uncomfortable shaking the hands of women not related to them. How it was verboten to sit in the front seat of a taxi, the front seat being reserved for the wife of the taxi driver and our presence there could be misconstrued as a sexual advance. How we should try to not touch the hand of a male cashier at a grocery store when he was handing over change, lest he view this as suggestive.

But the embassy guards, well, we did not need to worry about them; they had been thoroughly vetted, many had worked with Western companies in the past, some had even lived in America. Their English was better than the average Jordanian, and they were accustomed to our strange cultural differences, like American women wearing shorts and tank tops to the embassy gym (otherwise we were advised to never wear shorts and tank tops in Jordan).

There was the guard who showed me video of his son’s gymnastic competitions. The guard who handed candy to my daughter, his pockets crammed with single-wrapped mints. The guard who meowed because he’d seen us feed stray cats. I brought them cookies, bottles of water, chocolate bars. I would have my daughter present the treats, and the guards would direct their thanks at her, press their hands to their hearts, say “Alhamdillah,” or “Praise God,” pinch her cheek or ruffle her blond hair.

The guard who worked the gate closest to my house spoke very little English, and while I spoke very little Arabic we exchanged pleasantries almost every day. He was in his forties, clean-shaven, wore glasses, and would throw open his arms when he saw us. Most Jordanians said “You are welcome!” This guard would shout, “A million, million welcomes!” Then one of us would inevitably say something the other would not understand, we’d pantomime merrily for a few incoherent minutes, and I’d wave good-bye.

About a month after my husband left, my daughter and I came to this particular gate and found him on duty with another guard, a young man with beautiful green eyes whose English was better than most. The older guard reached into his back pocket as I drew close, produced a carefully folded piece of paper, and handed it to me. I hesitated, knowing this was out of the ordinary.

I opened the letter and began to read, the words in capital letters, the writing painstakingly exact:

You are beautiful. Your smile is the sun—

I looked up, startled, feeling a blush warm my neck. The guard was watching me, nodding. I glanced down to read more just as the younger guard tore the paper out of my hand. He began to yell at the older man in rapid, angry Arabic, pointing at the high embassy wall behind us, then stabbing his finger in the direction of my apartment. I froze, trying to keep a smile on my face and ignore whatever was going on.

The young man crumpled the paper in his fist. He stared with those green eyes into mine.

“He does not understand,” he said. There was something combative about his face, his words. I nodded, chastened, as if I did understand. I took my daughter’s hand and walked toward the embassy. Later, I exited the embassy by another gate, sneaking around to my apartment building without having to pass those guards.

He does not understand.

What could those words possibly mean? And how could I ever find out? He didn’t understand I was married? He didn’t understand it was odd for a near-stranger to tell a woman she was beautiful?

Or he didn’t understand that I smiled and chatted with everyone, that it wasn’t a declaration of affection on my part?

***

They relocated those guards.

I’d occasionally see the older guard at one of the farther gates. He always welcomed me but he did not put his arms out in the joyful way he had before; he did not say “A million, million welcomes!”

And he never wrote me a letter again.

How I wish I had held on to it, read it in its entirety, studied the intentions and misspellings. It could have been nothing more than a show of friendship, Jordanians often being more effusive than Westerners. I had strangers tell me I was like a daughter to them. Once, I spent a few hours with a woman and she yelled as I drove away, “I love you! I love you! I love you!”

He does not understand.

So I started writing a short story about Jordan as a way to figure it out.

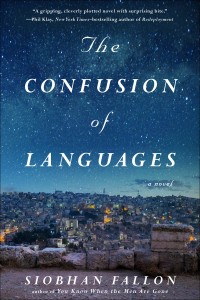

That story became a three-hundred-page book, The Confusion of Languages, and could have been much longer. All those endless opportunities for miscommunication.

I lived in Jordan for a year. While I never wore a tank top or sat in the front seat of a taxi, I’m still not sure exactly what I understand—not just about the Middle East, but about men and women. About people. About the ways we get one another wrong every day, about the moments that seem small but for some reason linger.

About all the fragile messages we want so desperately to share with another human being, only to find the distance is just too far, and it’s too easy to lose the words before we ever get the chance to read them.

***

For more of Siobhan’s essays, fiction, photos of Jordan, or to order copies of her new novel, The Confusion of Languages, please see her website: www.siobhanfallon.com