This interview first posted on the Military Fine Artists Network, or MilspoFAN, on January 31, 2017. Thanks for letting me repost here!

MilspoFAN: Tell us a little about yourself, your journey as a military spouse, and where you are today.

Siobhan: The journey has been a fairly scenic one. I met my husband in 2000, while I was bartending at my father’s Irish pub right outside the front gate of the United States Military Academy at West Point. My husband, KC, had just graduated and was staying on for a few months coaching soccer at the USMA prep school before heading to Fort Benning. I was working my way through getting an MFA in Creative Writing at the New School in NYC, and my future husband, hearing this, told me he loved to write. I’d met plenty of West Point cadets and soldiers and officers over the years, but this one won me over with talk of literature.

KC went to Fort Benning, Georgia, and then Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, and we were married on the beach in Oahu just before he deployed for a year to Afghanistan in 2004. I’m going to list the other posts we went to after getting married, it’s too exhausting to give a description of each and I have a feeling your readers know the deal: Fort Benning, GA (again); Fort Hood, TX (my husband did two year long deployments to Iraq during our three year assignment at Hood); Monterey, CA; Amman, Jordan; Falls Church, VA; and now we are in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

MilspoFAN: How has your role as a military spouse impacted your work as a writer- creatively, logistically, or otherwise?

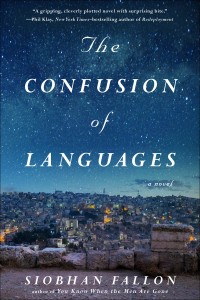

Siobhan: Well, creatively each post has been inspiring, and all of them are so vividly different from each other that I usually can’t help but write about them. I like to think that the settings of my work are as important as the characters themselves. All equally determine the story. Perhaps I take the adage “write what you know” a little too seriously? I enjoy examining the different ways people live, whether it be how people are on a military base vs. outside it, or how Western women living in the Middle East blend (or don’t) into a different culture. You Know When the Men Are Gone is set in Fort Hood, Texas, during a deployment of a brigade and I worked very hard to get the real Fort Hood, from the vast, scrubby firing ranges to the clever street names like Tank Destroyer or Hell-On-Wheels, into the stories. I’ve also written about Hawaii: one of the characters in You Know When the Men Are Gone met her husband when he was stationed at Schofield, and my story in the anthology Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War, is also set in Oahu. The new novel, The Confusion of Languages, takes place in Amman, Jordan, where my family and I lived in 2011. Of course we were stationed at all of the above, so I feel like the writing that came out of these places were gifts from the United States Army. It’s also helpful that a writing career is portable; I can take it with me no matter what corner of the world the military throws us into.

On the downside I inevitably miss opportunities in America. It’s difficult to do a reading or book signing at an indie book store in Chicago when you live in Jordan or Abu Dhabi. And while planning the release of my new novel this summer, I know I have a very small window of time when I will be on U.S. soil during the school break of my small daughters. Combine that with the responsibilities of seeing family and friends, who I usually only get to see once a year, and my blood pressure starts to rise with thoughts of all the ground I have to cover in a such a short amount of time. I really have to be focused about what I can accomplish in advance, and get the word out as much as possible before I even get on a plane. Naturally, I also participate in fewer panels and conferences than I would like because of the tremendous distance. But every once in a while some generous writing program will send me a plane ticket, and of course there is social media, email, and Skype for staying in touch with readers or book clubs.

My husband is very supportive and there are times we can work in an extra trip stateside for me, as long as we can balance childcare and travel expenses with his long work hours. So yes, the distance and unpredictable nature of military life does make it more difficult. You do what you can. We military spouses know how to roll with the punches, and my family and I have been pretty darn blessed with some excellent locations. So like everything in life, it’s a trade off.

MilspoFAN: Of your 2011 work, You Know When the Men are Gone, the New York times wrote “This lean, hard-hitting short-story collection outshone some of the year’s most imposing doorstop-size novels.” How does your writing style and writing process for your first work of short stories compare to your upcoming full-length work, Confusion of Languages?

Siobhan: A novel is a pain in the ass. Honestly, I didn’t think I had any idea how hard it would be. I thought going from stories to novels was a natural progression, something that I’d be able to do without much effort, especially after I practiced so much by writing all those lousy novel drafts that are still lurking on my old hard drives. Right? And everyone was always telling me that my stories read like small novels, and that they wanted more. So I thought I’d just write, you know, more, as in a really, really long short story. HA!

You can read a short story in one sitting. Of course there are things that happen off the page, but the author can keep track of every detail in thirty pages, sometimes to the point where I remember whole snatches almost word for word. You can sit down and sip your coffee and read and say aha! I need to change this and this and then go get another cup of coffee and come back and make those changes. Thirty pages is a small town with a no name grocery store. But three hundred pages! I could never get my mind around the three hundred pages. Three hundred pages is New York City on New Year’s Eve. You can’t possibly keep track of what made it into the novel or not in one sitting, especially after all the editing and rewriting and gnashing of teeth. There are notebooks and index cards and piles of drafts taller than your four year old daughter of everything you deleted and reinserted and deleted again, how can you possibly remember everything?

But you do it. It takes time. Painstaking editing and screaming at your children not to come in and disturb Mommy again for another damn cup of apple juice! You feel like the worst writer (and mom) in the world and the biggest failure and no one will read you and those who do won’t ever be able to look you in the eye again because now they know you have absolutely no talent—and then you write the most beautiful paragraph you have ever written, or figure out why one of your characters behaves in a certain way, or how this one very important plot line can tie seamlessly into another. And that epiphany keeps you going. And when all those terrible thoughts seize your brain again, amazingly enough another epiphany will smile at you.

You need to remember that the things you want to say are there on the page, black and white and real, and it’s worth all the self doubt and agony and hangdog looks of your poor neglected children. Tomorrow you will take the kids to the park, you promise! Writing should be hard. Readers are going to dedicate hours and hours, days maybe, of their precious lives, reading what you have penned, letting your words fill their heads and linger in their thoughts. Those words better be your best.

MilspoFAN: What’s next for you?

Siobhan: The new novel, Confusion of Languages, will be out June 27, 2017. It started as a short story I wrote in Jordan in May of 2011. That means it’s taken me about six years. Dear God, that’s the first time I’ve done the math. SIX YEARS!! Plus more rewrites than I could even count at this point. I’d started each rewrite from scratch– I’m talking blinking cursor on a blank computer screen, five, six, seven times. I would work from a draft that I printed out (300 $%#@ pages!) next to my computer, but I would retype everything all over again because it felt like the only way to really be in the story, to allow myself to write new material and edit/ catch every nuance of the material I might want to reuse/retype. When I just cut and paste, I feel like I am less critical, I don’t get seized by words in the same way or see the story as something malleable that I can drastically change if need be.

That said, now I’m taking a little bit of a break. It feels good to let new ideas sort of well up in me again, rather than focusing so completely on The Confusion of Languages. I’m writing some non-fiction essays about life in Jordan, thinking about ideas for future projects, letting this incredibly weird and wonderful world of Abu Dhabi inspire me. But it’s nice to not be caught in the thrall of something as overwhelming as working on a novel, if at least for a little while.

MilspoFAN: Is there anything else that you would like to share with MilspoFAN readers?

Siobhan: Reach out to other Military spouses who are in the arts as much as possible. There are more of us than you think. And we are pretty freaking fantastic! Read Andria Williams most excellent blog Military Spouse Book Review (https://militaryspousebookreview.com/),every word that lady writes is brilliant (you should see her Lego creations) but Andria also shares the space with other mil spouse writers who chime in to review books or write blogs of their own on her page. It always feels good to know we’re not the only ones who worry about these insane mil lives of ours. For something a little more ‘highbrow’ but definitely worth being aware of, I recommend Peter Molin’s blog Time Now (https://acolytesofwar.com/), which reviews all military related arts, from photography to film to writing to dance to theater productions. Molin is incredibly supportive of mil spouses as well as female vets, so it’s not just a list of macho men war novels, if you know what I mean (I’m sure those of you who married to infantry men like me know exactly what I mean).

I want to thank you, Jessica, and I also want to thank all of you who are reading. We need to support each other, and this site is doing that beautifully. We are far flung, we don’t have the natural support system of the home town neighborhoods where we grew up, the libraries and churches and cafes and town halls where we could gather and spread the word about our different projects, so we have to improvise and create our forums online, in places like this. So let’s spread the word and support each other here, and show everyone how much mil spouses have to offer, how we’re not at all the way stereotypes paint us to be, how diverse and talented and amazing we can be.

MilspoFan: https://milspofan.wordpress.com/

Time Now https://acolytesofwar.com/

Military Spouse Book Review https://militaryspousebookreview.com/

Learn more about Siobhan’s books at: http://siobhanfallon.com/books.html

Excerpt from You Know When the Men Are Gone, Siobhan Fallon

Three a.m. and breaking into the house on Cheyenne Trail was even easier than Chief Warrant Officer Nick Cash thought it would be. There were no sounds from above, no lights throwing shadows, no floorboards whining, no water running or the snicker of late-night TV laugh tracks. The basement window, his point of entry, was open. The screws were rusted, but Nick had come prepared with his Gerber knife and WD-40; got the screws and the window out in five minutes flat. He stretched onto his stomach in the dew-wet grass and inched his legs through the opening, then pushed his torso backward until his toes grazed the cardboard boxes in the basement below, full of old shoes and college textbooks, which held his weight.

He had planned this mission the way the army would expect him to, the way only a soldier or a hunter or a neurotic could, considering every detail that ordinary people didn’t even think about. He mapped out the route, calculating the minutes it would take for each task, considering the placement of streetlamps, the kind of vegetation in front, and how to avoid walking past houses with dogs. He figured out whether the moon would be new or full and what time the sprinkler system went off. He staged this as carefully as any other surveillance mission he had created and briefed to soldiers before.

Except this time the target was his own home.

. . .

He should have been relieved that he was inside, unseen, that all was going according to plan. But as he screwed the window back into place, he could feel his lungs clench with rage instead of adrenaline.

How many times had he warned his wife to lock the window? It didn’t matter how often he told her about Richard Ramirez, the Night Stalker, who had gained access to his victims through open basement windows. Trish argued that the open window helped air out the basement. A theory that would have been sound if she actually closed the window every once in a while. Instead she left it open until a rare and thundering storm would remind her, then she’d jump up from the couch, run down the steps, and slam it shut after it had let in more water than a month of searing-weather-open-window-days could possibly dry.

Before he left for Iraq, Nick had wanted to install an alarm system but his wife said no.

“Christ, Trish,” he had replied. “You can leave the windows and all the doors open while I am home to protect you. But what about when I’m gone?”

She glanced up at him from chopping tomatoes, narrowed her eyes in a way he hadn’t seen before, and said flatly, “We’ve already survived two deployments. I think we can take care of ourselves.”

Take care of this, Nick thought now, twisting the screw so violently that the knife slipped and almost split open his palm, the scrape of metal on metal squealing like an assaulted chalkboard. He hesitated, waiting for the neighbor’s dog to start barking or a porch light to go on. Again nothing. Nick could be any lunatic loose in the night, close to his unprotected daughter in her room with the safari animals on her wall, close to his wife in their marital bed.

Trish should have listened to him.

. . .

This particular reconnaissance mission had started with a seemingly harmless e-mail. Six months ago, Nick had been deployed to an outlying suburb of Baghdad, in what his battalion commander jovially referred to as “a shitty little base in a shitty little town in a shitty little country.” One of his buddies back in Killeen had offered to check on Trish every month or so, to make sure she didn’t need anything hammered or lifted

or drilled while Nick was away.

His friend wrote:

Stopped by to see Trish. Mark Rodell was there. Just

thought you should know.

That was it. That hint, that whisper.

Mark Rodell.

Coming June 27, 2017:

Excerpt from The Confusion of Languages, Siobhan Fallon

We are close, so close, to Margaret’s apartment, and I feel myself sink deeper into the passenger seat, relieved that I have succeeded in my small mission of getting Margaret out of her home, if only for a few hours. The day is a success. Sure, I

had to let her drive, something I usually avoid. Margaret is always too nervous, too chatty, looking around at the pedestrians, forgetting to put on her signal, stomping on the brakes too late. But today I actually managed to snap her out of her sadness.

I have done everything a good friend ought to do.

It’s not until we reach the intersection at Horreyya and Hashimeyeen that I realize my mistake. I’ve misjudged the time, something I never do. Friday prayers have already let out. We’d stopped by the ceramics house to pick up a box of pottery I’d

ordered and Margaret, being Margaret, sat down for too long with the hijab-ed women at their worktable, letting them touch Mather, pinching his cheeks and thighs, rubbing silica dust all over his tender baby skin. Now the intersection ahead is congested, chaotic. I see men strolling from the mosques, climbing into the cars they triple-parked along the main road.

I sit up straight, the seatbelt pressing against my chest. The traffic light turns yellow as we approach and cars alongside us speed by. Margaret could step on the gas and easily make the light but both of us see a man on the sidewalk, waving his

entire arm in the air.

“Just go—” I urge, but Margaret shakes her head, slowing the car, the corner of her mouth turning up.

“It’s uncanny how he always spots me.” She says something like this every single time and I usually reply, The man’s livelihood depends on his ability to spot the softhearted suckers. But today I am silent. Mather shouts from his car seat but she ignores him too.

Her window is down before we’ve come to a complete stop. The man reaches into the cluster of dented white buckets at his corner-side stand, pulls free a few dripping-wet bouquets, then dodges traffic until he’s at Margaret’s side. He leans through the window, wearing a red and white checked kaffiyeh around his throat. Margaret’s wallet is on her lap, ready.

“Hello, baby!” the man shouts at Mather, avoiding looking at both of us women with our loose hair and bared elbows. His flowers are spread perfectly across his arm, inches from the very face he will not to peer into. The car fills with the scent of crushed rose petals, exhaust, and his sweat, a faint mix of onions and soil. I do not point out that most of his offerings are wilted, tinged with brown. I notice the cluster of pristine white blossoms at the same time Margaret does, fragile, lacy blooms on very green stems, and she nods toward them, holding up her money. It takes only seconds.

As he passes the chosen bouquet to Margaret through the window, Mather yells again from the backseat, wanting something; that child is always wanting something. The man turns to the baby but he doesn’t stop there; he lifts his face and stares behind our car, his brown eyes widening with fear as he stumbles backward. Before I can look around, there is a ripping scream of brakes and our car leaps forward with a thud of crushed metal. Our heads rock on our spines and there are flowers in flight across the dashboard, white blossoms spread open like tiny, reaching hands.

#confusionoflanguages

It’s time for the PAPERBACK release, my friends!

It’s time for the PAPERBACK release, my friends!