Auld Lang Syne

(An earlier and shorter version of this post appeared in the Military Spouse Book Review: Happy New Year! Let’s Read!)

Well, friends, 2019 was the year I became a crazy person (or perhaps a crazier person?). This fiction writer, who spent a lifetime cultivating a cool indifference to military history, suddenly became rabidly obsessed with the life and times of General George Armstrong Custer and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. I joined niche Facebook pages (full of lovely, brilliant people) and paid dues to associations, covered the walls of my office with photographs and maps, and have bought, at my last count, more than one hundred and twenty-five books that deal with the particulars and participants of the battle.

And the reason I became so disturbingly hooked?

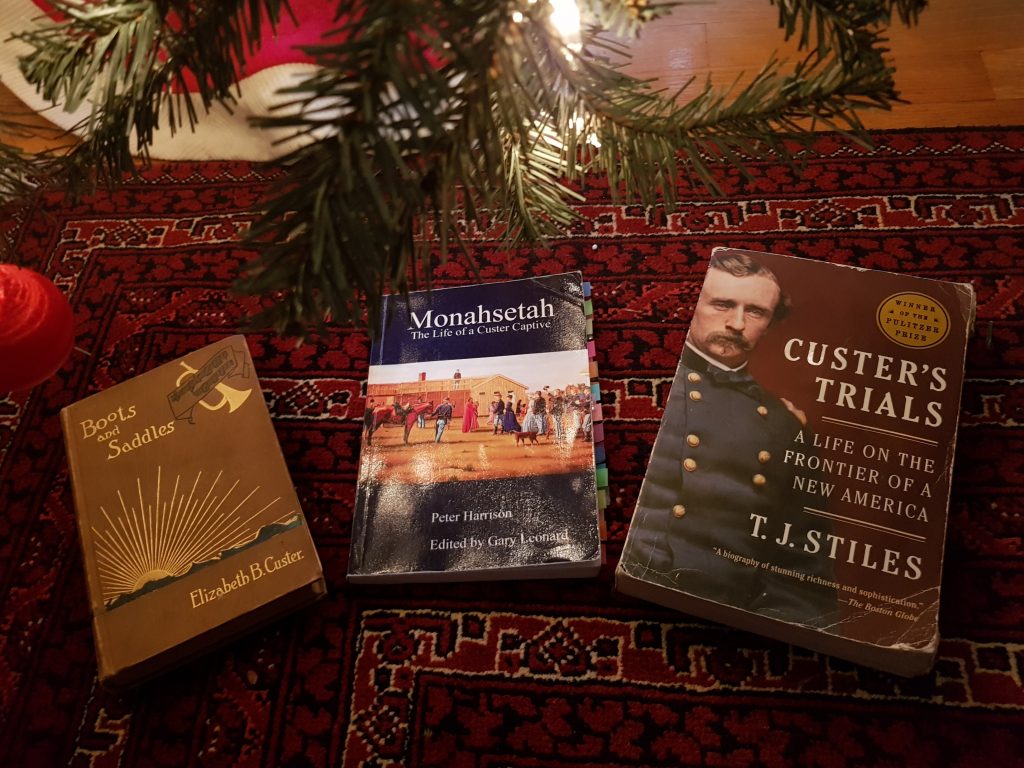

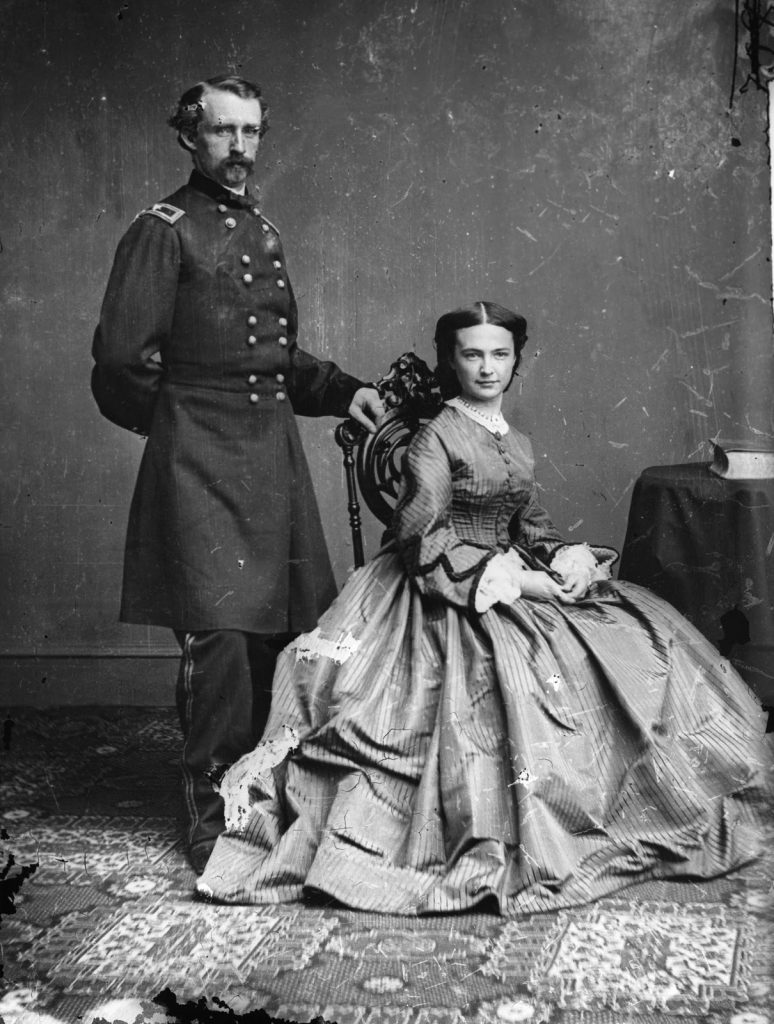

Because of Elizabeth Bacon Custer, the feisty, charming, smart, and tiny spouse to the above mentioned general. I happened upon the Wikipedia account of her devoted life, went down every conspiracy theory rabbit hole surrounding the hotly contested accounts of what happened at the Little Bighorn, and am currently working on a novel about her life and times. The three books pictured above illustrate why I have become so obsessed, and why I just can’t stop reading Little Bighorn related materials…

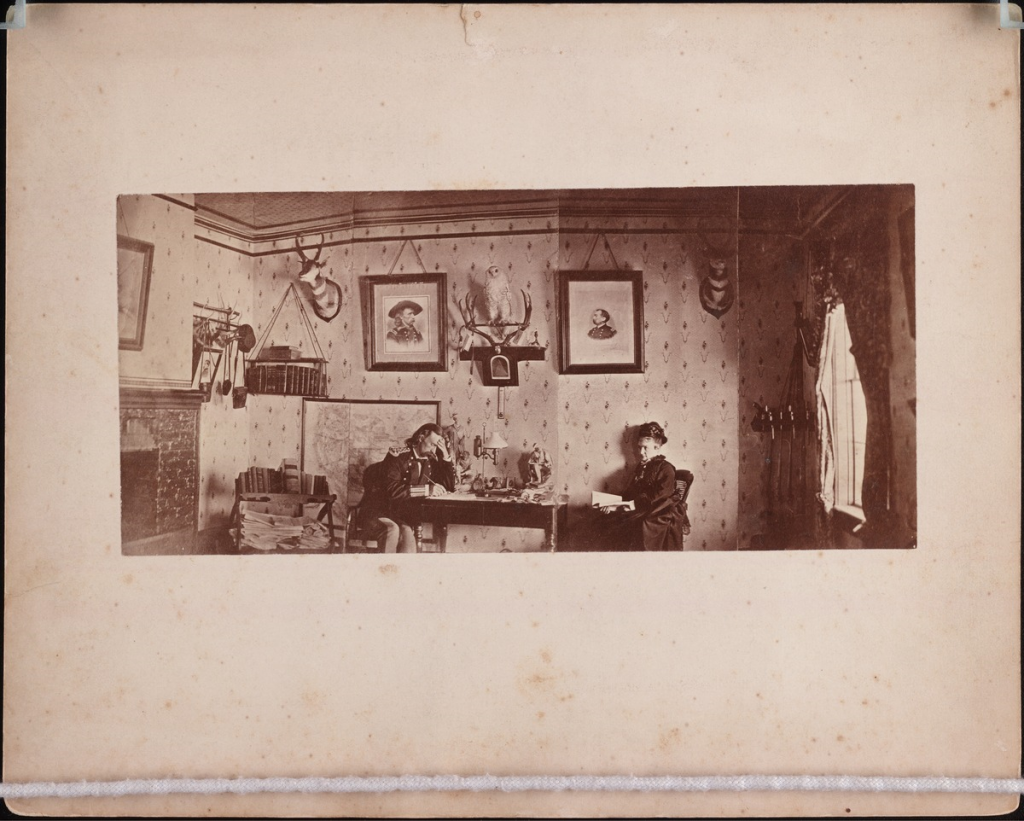

Libbie followed her husband from the outskirts of Civil War battlefields to icy prairies, proud to be one of the only spouses allowed to always travel with the men. From drafty, inhospitable, barren forts, she watched grasshoppers eat every green thing for miles, learned to put gun shot in the hem of her skirts to keep them from whipping around her head, and wrapped herself in fabric, head to toe, to keep out vicious mosquitoes during hot summers. She met Presidents, Russian counts, Native American chiefs, was shot at, and helped save drowning soldiers during an apocalyptic Kansas flood. At a time when the Army gave no allowances for spouses and food was scarce, she found a way to scrape together and create festive dinner parties, plays, musicals, and military balls.

When her husband died at the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876 (with more than 300 men in his command), Libbie was determined to defend his reputation and did so until her own death, nearly fifty-seven years later (she never remarried). Part of that effort included writing three memoirs (THREE MEMOIRS!!!), the first of which, Boots and Saddles, is my favorite. Self-deprecating, funny and brilliantly insightful, bringing to life a military world that feels closer to Little House on the Prairie than any base I have ever seen, the woman was a natural-born writer.

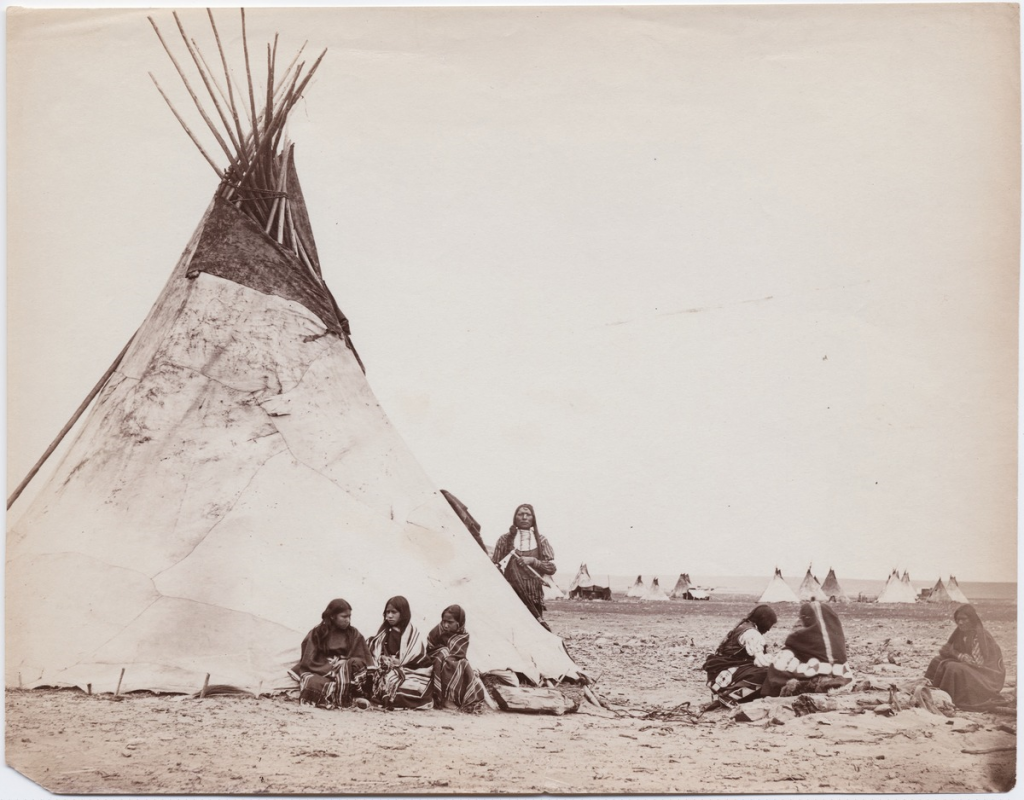

If you are curious to read the flipside of Libbie’s idyllic memoirs of life with her fun-loving husband, as well as insight into life on the plains long before U.S soldiers built their ‘war houses’ or settlers homesteaded (and often trespassed), I recommend Monasetah: The Life of a Custer Captive by Peter Harrison, edited by Gary Leonard.

In November, 1868, George Armstrong Custer and the Seventh Calvary attacked a village of Southern Cheyenne on the banks of the Washita River in Oklahoma. They took fifty-eight women and children captive in an effort to leverage other Cheyenne and Native American tribes to move into the reservations. Harrison and Leonard present a very compelling case that Custer chose one of the captives, Monasetah, the daughter of a chief killed during the Washita Battle, as his lover. Monasetah stayed with the Seventh Cavalry for the duration of the time these Cheyenne were held by the U.S Army (from November 1868 until April 1869), accompanying them for a long winter scout to Texas, and helping negotiate the freedom of two white female hostages from a Cheyenne village. She is mentioned and noted for her beauty in both Custer’s own memoir, My Life on the Plains, as well as in Libbie’s books (though any intimate relationship with Custer is not, of course). But more than allotting Monasetah a mere footnote in white American history, she is developed as a bold and capable woman, offering insight into the day to day life of the Southern Cheyenne before their roaming ways were taken from them.

Lastly, Custer’s Trials by T.J. Stiles, is the perfect bridge to the books above. The Pulitzer prize winning author’s sweeping biography not only reveals Custer to be heroic, contradictory and deeply flawed, but also illuminates how fraught and at odds the United States of America were during the bloody years between the Civil War and the Indian Wars. Covering our government’s many failures during Reconstruction and our shifting policies and ‘treaties’ with Native Americans, lit through with gorgeous writing and anecdotes that breathe, I felt like I relearned a vital but often overlooked period of my country’s history.

…

Siobhan Fallon is the author of You Know When the Men Are Gone and The Confusion of Languages. For more on her current Custer craziness, please follow her on Facebook and Instagram, or check out her website at www.siobhanfallon.com